Klan connection prompts community conversation

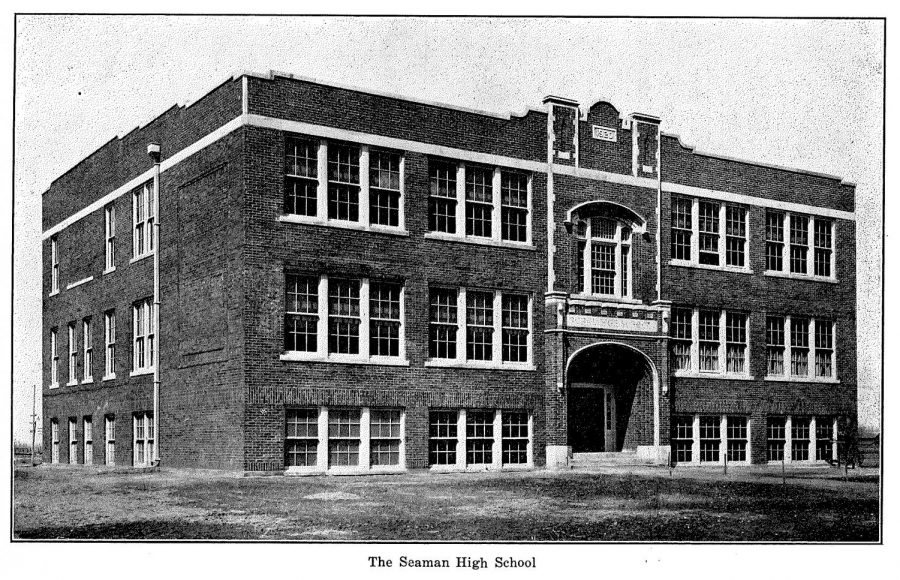

To the 1926 high school yearbook staff, Fred Seaman was a savior.

They fawned over their well-adored principal in a dedication that read: “To a man who is dauntless in character, far-sighted in vision, ever loyal and ever sacrificing, the pupils of Seaman High School wish to express their gratitude and appreciation.”

It was also a dedication to a man who in that same year was referenced several times in area newspapers as a leading figure in the Topeka Ku Klux Klan — a legacy that 95 years later, the school community he left behind is still trying to unravel.

Fred Seaman was involved in the Klan as an exalted cyclops. As stated in “Klansmen’s Manual” published at the library archives of Michigan State University, this would have made him a “Regimental Commander” in the area. He would have overseen a staff of officers and aides to assist him in duties.

Though Seaman died in 1948, his role as a Klan leader has caused some to question the current values of the district. Members of the surrounding community are left wondering how to approach an issue as considerable and far-reaching as Fred Seaman’s past. The solution is a seemingly simple yet complex task: creating a real conversation.

“For the [district] community to emerge whole, you not only have to get the bad stuff out, but you have to infuse it with good healthy cells,” Washburn University assistant history professor, Mr. Bruce Mactavish said. “You can’t ignore a cancer as you cannot ignore a racist past and think by ignoring it that it doesn’t exist.”

Ku Klux Klan activity in Topeka and Kansas

For that discussion to occur properly, understanding the background of the Ku Klux Klan in local affairs is crucial.

According to Mactavish, the second wave of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, much like its 19th century counterpart, considered only people who were native-born, white, and Protestant to be whole. Therefore, they specifically targeted Catholics, Jews, Italians, Hispanics, African Americans, and many others due to their perceived inferiority.

“There were acts of anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, and anti-Black violence all along the eastern corridor of Kansas from Coffeyville all the way up to Kansas City,” added Mr. Shawn Lee Alexander, a professor of African and African-American studies at the University of Kansas.

The Ku Klux Klan of Topeka was active in its pursuit of control and influence within the local community. Mr. Mactavish explained that local Klan members regularly dressed up in their robes and drove through African American neighborhoods in the city or stalked around the edges of town to find a young couple on a date, and disturb them by means of flashing their lights or knocking on the window.

Topeka Klan members also gathered to use typical symbols of Klan actively. At an initiation meeting which took place in Topeka the Emporia Gazette reports in March of 1923, “A crowd estimated at 1,000 men gathered in the glare of a flaming cross three miles north of Topeka.”

The Kansas Klan soon caught the attention of the courts. Charges arose, not from any of these attempts of intimidation, but from the fact that Kansas Klansmen were using a Georgia business charter in place of creating a Kansas-specific corporation. The out-of-state corporation was not legally permitted to organize Klan lodges and directly sell paraphernalia to Kansas Klan members due to interstate commerce laws.

William Allen White, editor of The Emporia Gazette at the time, and Governor Henry Allen began to push back on the Klan for its lack of a legal charter, using it as grounds to kick the Klan out of the state. Eventually in 1927, Kansas became one of the first states to officially outlaw the Klan.

Even so, the Klan was not completely eradicated.

“Everyone will look at that and praise Kansas for being one of those first places that ban the organization,” said Dr. Alexander. “But they ban the organization because they have a technicality to get them out of the state and [the Klan] still existed after.”

Unique circumstances lead to complications

Seaman’s Klan leadership has become a groundbreaking topic of various opinions for not only a small community, but a whole country.

Information was released at a time when the nation is facing the revisitation of many namesakes in similar situations. Americans have seen a rising number of stories concerning topics such as offensive school mascots and educational institution founders who championed slavery or the Confederacy.

“It’s bigger than you, me, the board, the administration at the high school — it’s just bigger,” school board president and long-time district resident James Adams said. “People need to have their voice heard, give their opinions, and talk about it.”

The most considerable issue that has formed over the release of information is Seaman’s namesake; to replace it or leave it as is. Many community members are awaiting the chance to voice their opinions on the possibility of a name change in light of Fred Seaman’s Klan leadership.

A prominent feature that sets Seaman USD 345 apart from other school organizations reconsidering their names is the widespread use of the Seaman name. That name, a community marker of sorts, now adorns several area institutions, including the Seaman Gardens residential area, the Seaman Community and Seaman Southern Baptist churches, the Seaman Food Mart gas station, and more. A street right next to the Seaman Education Center is itself emblazoned with the word Seaman.

“People have added it as so much of our DNA,” said Adams. “Nobody says I live in North Topeka, people say I live in the Seaman school district.”

Upcoming Meetings addressing the community

Decades after Seaman’s death, in-depth conversations surrounding his legacy as a Klansman are only beginning. The Seaman Board of Education has committed to holding events and conversations to discuss Fred Seaman’s past, although no specific conversations are yet in the works.

The first of those efforts is “Race Relations in the Seaman Community: A Frank Conversation,” a virtual event that will be hosted by the school board Monday evening. The agenda for the meeting is to address current issues of racism within the district, although the issue of Fred Seaman may come up as well. The meeting will allow current students to speak out about their experiences and for community members to voice their concerns going forward.

Board member Frank Henderson and history teacher Nathan McAlister will help lead Monday’s conversation.

“When you look at the demographics of our district, it is clear that we are very caucasian,” said Henderson. “I do not believe there is a keen awareness of the needs and experiences of students of color. True inclusion cannot be achieved until we address many areas of equitable opportunities and needs of all students.”

Olivia Oliva, an Asian American junior at Seaman High School, is highly involved in the preparation for the Monday meeting. She said she has had frequent experiences with racism last year. She explains that her Chinese I class last year was supposed to be all about being a part of and learning Chinese culture.

But she recalls her experience as so much worse.

“I had never faced so much racism and discrimination in my life as much as I had in that class,” Oliva recounts instead.

Moments of racial discrimination are seen and experienced by many of the students of color at the high school. Some examples of the racism students of color face at SHS include inappropriate “jokes” focusing on students’ ethnicity, comments which question a students’ appearance, and remarks relating to a racially-charged stereotype.

Students of color see cases of racism regularly around the highschool ranging from every couple of months to daily. The number of occasions is lower this year in particular; in students’ opinions, COVID-19 limitations on interaction are attributing to the reduction this year.

“I feel like it’s been all throughout my time at Seaman where I have heard different things,” says sophomore Ishta Wabaunsee, a Native American student.

Fred Seaman once delivered a speech in the midst of his campaign for the superintendent of public instruction. According to The Topeka Daily Capital in a June 1922 newspaper, “his talk was mainly devoted to a program for Americanization in the public schools of Kansas.”

A 1920s pamphlet located at the Kansas Historical Society called “America for Americans” within the same time period sheds light on what Americanization meant within the KKK.

It states that America’s “blood be not polluted, but kept pure as a sacred heritage and thereby forge on to front and take its place at the pinnacle of all nations of the world, where purity, Christianity, peace and prosperity reign supreme.”

Oliva relays, “Truthfully, for the kids who are people of color at the school, it’s very hard to be able to go to a school that is based on this person’s values of hate and intolerance to people like you.”

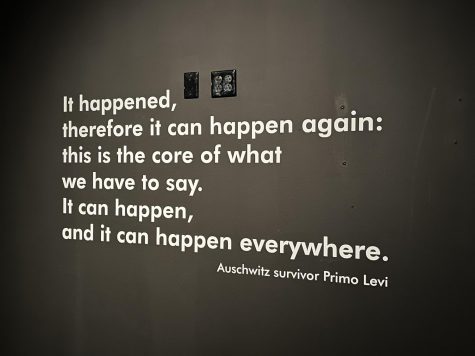

A conversation is necessary for finding a way forward in the district despite the discomfort such a conversation will bring.

“The founding of our district and the KKK involvement would like to be erased by some individuals. Some have suggested we ignore it and move on,” says Mr. Henderson. “However, it is critical that we recognize, explore, examine and acknowledge our history as a district and a community. Once we do that, we can determine if and how it impacts who we are today and what steps should be taken.”

The school community itself needs to have an opportunity to discuss this confirmed information. Otherwise, the district is willing to ignore controversial information in the same manner that an entire community had almost a century ago.