Equity Action Network aims to mend racial issues, despite district’s historical struggles

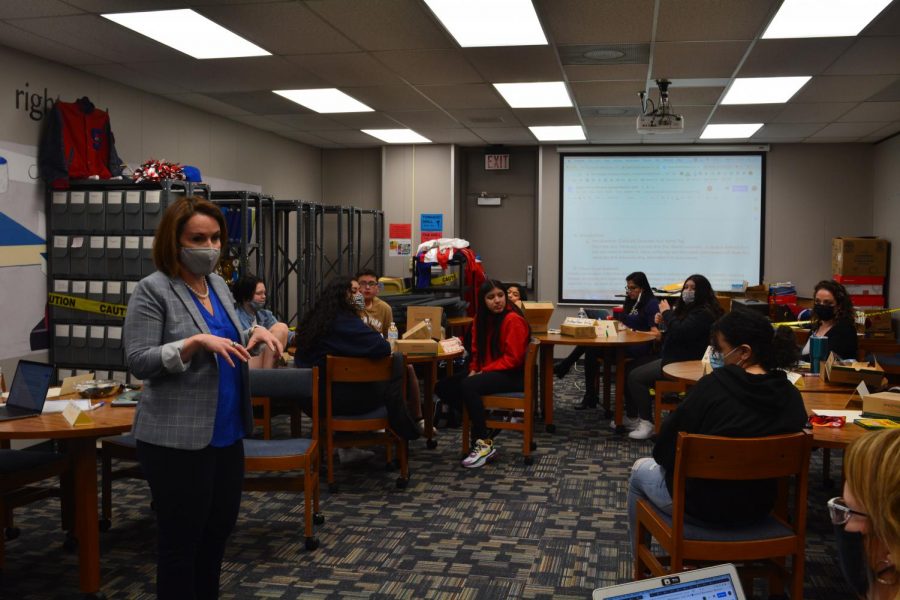

Administrator Danira Fernandez-Flores speaks to students about identifying themselves through name tags. The main meeting discussion would surround emotions encompassing the possibility of a district name change.

Seaman High School students are continuing to break down racism within the district population through a student-focused group called the Equity Action Network.

The group formed in preparation for the “Community Conversation: Race, Equity, and Moving Forward Together” meeting on December 7th of last year with a goal in mind — community inclusion for students of all ethnicities.

Instead of stopping the discussion after the district-wide gathering, meetings have continued for an hour every Wednesday, aided by the flexibility of fully remote learning mid-week.

Teachers anchor a safe atmosphere for speaking and standing up

Twenty-one Seaman High School students currently participate in the EAN group, and district personnel ranging from teachers to administrators manage and assist with their meeting agendas.

A typical group meeting consists of an opening topic to stimulate conversation, thought, and listening between the leaders and students, and then discussion of a main subject for the rest of the meeting.

Lisa Martinez, Seaman High School Spanish teacher and sponsor of the Equity Action Network,

emphasizes that each of these discussions is necessary and meaningful to the network of students of color who share their experiences and emotions behind discrimination.

“Most students of color — in my observation — are pretty nervous to speak even with their peers about their experiences because I feel that they live in a sense of always protecting themselves either within a peer group that looks like them, or within a group where they don’t express a lot about their ethnic or racial identity,” said Martinez.

“And they shouldn’t have to feel that way.”

Activities that generate cultural conversations take place through a wide range of forms. It can come from name tags culturally embellished with drawings or unpacking personal experiences with racism inside the school grounds to create steps of healthier action.

Shifting from inner-city school life to learning in a rural setting, Senior Morgan White, who has a biracial background of both Black and white, said that it has left her feeling as though she is clashing throughout the district. She senses that the group has given her a place within the community to feel included.

“I’ve noticed a lot of (people) not necessarily thinking that I know what I’m talking about always,” White said. “Not really always thinking I’m wrong, but often thinking that I’m wrong with what I’m doing.”

As for junior Emma Simpson, she said she enjoys being a part of the meetings as a white ally to understand the experiences of students of color in a community that is not that diverse.

“I would like to learn more about minority struggles in the community and learn ways I can help,” said Simpson “Whether that’s uplifting voices or simply listening to others.”

Students of color were integrated into the high school, but not without issues

No type of group space existed for students to relay their race-related issues and concerns until the Equity Action Network came to fruition early on the last fall.

When the district was first founded in the 1920s, laws of the time allowed for students of any race or ethnicity to attend in the district. Indeed, photographs in earliest yearbooks and school documents show students of color were in attendance .

However integration was not a choice for the district — but rather a legal requirement .

In the decades prior to the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education case, centered around the neighboring Topeka USD 501 district, African American students were increasingly excluded from white schools.

Jean Van Linder’s article titled “Early Civil Rights Activism In Topeka, Kansas, Prior to the 1954 Brown Case” states, “A consequential and direct response to the Exoduster movement was the modification made to the color line in 1879 law permitting segregation in elementary schools in cities of the first class, or those with a population over 15,000. In 1879 only three cities were large enough to legally segregate: Leavenworth, Atchison, and Topeka.”

At that time the Seaman Rural School District was on the outskirts of Topeka, leaving it necessary by legal measures to integrate the student population.

Early usage of minstrel showcases misunderstanding of ethnic groups

While the Seaman district may have been integrated, an inclusive environment was not necessarily a part of the district’s early history, as demonstrated by the high school’s clubs and sports. Extracurriculars of the district implemented practices that marginalized students of color.

This marginalization seeped into the district early on through blackface minstrel performances called “High Brown Breach of Promise” taking place in April of 1923.

“The dramatics have succeeded unusually well financially owing to the fine coaching of Mr. Seaman and the determination of those taking part,” a female student’s journal titled “A Girl’s Commencement” described.

The journal further explains, “The overture comprised a number of old-time melodies that were sung by the group of black-faced singers. There were thirty who took part in this opening number.”

Associate Professor of History, Dr. Kelly Erby of Washburn University explains that blackface has long been used to culturally appropriate, meaning when one culture steals things from another culture undergoing oppression. She explains that it creates an economic disadvantage over the oppressed group, reinforces power imbalance to the dominant group, adds to stereotyping and a hostile environment for the non-dominant group.

“The black face is accompanied by behaviors that perpetuate racism because they portray people of color through negative stereotypes as unintelligent, lazy, silly, hyper-sexual, lying, boorish, drunks, and more, said Dr. Erby.

“Above all, blackface reinforces white supremacy.”

Productions of the mocking shows persisted along with the attempts of the district to blend their rapidly diversifying population.

In the 1949 yearbook, Seaman High’s pep club elected the school’s first Black homecoming king in what would appear to be a relatively progressive step toward inclusion in pre-Brown v. Board times.

Hardly a year later, though, the high school’s drama club continued with minstrel shows, as seen in the subsequent yearbook. A photograph in that yearbook shows a student, whose face is nearly completely covered in black paint, impersonating a Black man in a one-act minstrel show called “Spooks & Hootin’ Owls.”

Seaman High School tussles with leaps forward and back with racial justice

The acting within minstrel shows eventually disappeared as a focus of the high school drama club.

But other racist or insensitive events continued.

In 1991, StuCo held an annual “Slave Day” where students could “own” other students for school hours, the high school yearbook shows. A particular photo even displays a student “being fed by his owner” with a banana on the event day.

Racial tensions called for an elective course dubbed the Race and Ethnic Studies class, which Powerschool records indicate started as early as 1991, although the course did not reach school catalogs until the 1994 to 1995 school year. The staff aimed to implement the course as a tool to educate the student body on a variety of races, ethnicities, and cultures in standard Social Studies courses.

In 1996, racial tensions rose again when USD 345 was identified as the only school district in the county that didn’t observe Martin Luther King Jr Day, resulting in approximately 80 students walking out of class an hour early in protest. As punishment, students were given the choice of either serving a half-hour of detention or writing a 300-word essay on why they felt the district should observe the holiday.

Students are working towards resolutions in the present and onward

Though the Equity Action Network plans to expand their outreach in the future, the organization is seeking to manage discrimination situations before working outside of the group.

“I think it’s important for everybody to know that it’s a baby organization that has plans to grow, that is still very much so getting started and exploring who they are as an organization or we are as an organization,” said Martinez.

Eventually, Martinez believes that the group will seek to establish direct mentorships between students of color and professional leaders of color in the Topeka community, and even evaluate traditional school events to ensure their inclusivity.

“I feel like if (EAN) is successful, that we’ll be able to expose people to different problems that people of color are going through in the district — expose them to what they may or may not know that they are doing wrong, and help them fix it and make themselves better people,” White said.

Joining the Equity Club

If a student is interested in joining the Equity Action Network, reach out to Mrs. Martinez at [email protected].